How To Make Your Own Language in 4 Easy Steps

Alright, my friend. You came here looking to learn how to make your own language, more lovingly known as a conlang. So exciting! A language all your own! Well I have some good news and some bad news.

The good news is that you just need four things: phonemes, a writing system, grammar rules, and a dictionary. Piece of cake.

The bad news is that, if you’re like me, you will never escape the fascinating world of linguistics. The phonemes, glyphs, and writing systems you learn here will haunt your dreams into the eternities.

So, as long as you fully accept that this will grab hold of your very soul and cause you to rethink the very sounds that come out of your mouth on a daily basis, then we should be good to go.

But you already knew that, didn’t you? You’re here because you’re already hooked. So let’s get started.

What is a Conlang?

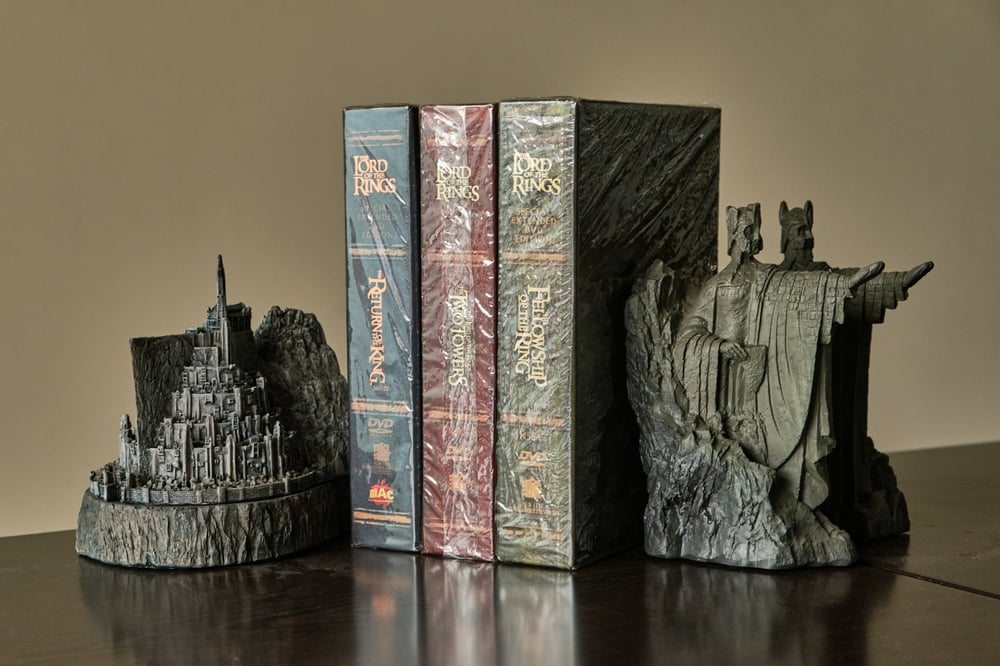

A conlang is a CONstructed LANGuage. Made popular by J.R.R. Tolkien and the creators of the TV show Star Trek, these languages are fully fabricated by true language artists.

Elvish, Klingon, and Dothraki are the languages you have likely heard the most about, but there are quite a few constructed languages out there.

And today you will join those legendary language artists.

Creating Fictional Languages

Let’s be real: the best way to learn is by doing. So we will create a conlang here and now. Starting with the very first step.

Phonemes

It all begins with sounds. We have to select what sounds we want to include in our language. These basic sound components of speech are called phonemes.

I’m going to introduce you to your new best friend, but you’ve got to come back here so we can finish going over the rest of this conlang work. You promise you’ll come back? Who am I kidding, you’ll probably be gone for a couple hours. Just come back once you’re done.

Meet the IPA (international phonetic alphabet.) Go to the link below, click on each letter and hear all the wondrous sounds that we can make.

Good, you’re back. Now I know what you’re thinking. How the fricative are you supposed to choose between all these amazing sounds for your conlang?

I can’t make that decision for you, but I will say that I find it easier to select vowels first and then consonants. We don’t have time to get into the differences between plosives, nasals, and approximants, so I’ll leave that to your own research. For now I’ll select some vowels for this language we are creating.

Vowels

I (ee)

o (oh)

ʌ (uh)

a (ah)

e (eh)

We will stick to these five. Perhaps the number five holds some significance to this culture, and so there are only five vowel sounds that are used.

Consonants

Sticking to that theme, I’ll choose ten consonants. Two sets of five. We will determine rules for each set later.

d (as in day)

k (as in cat)

m (as in marry)

N (as in dung)

Θ (as in fell)

r (as in burrito. This is the rolled r. Or the trill r.)

ʃ (as in rush)

ɭ (as in lower)

β (as in over)

b (as in bury)

Many of the sounds I selected are English sounds or close to English sounds for simplicity. But I’d encourage you to dig into sounds that are different from the ones you are used to. Also fun to consider is that these are just human sounds. If you are creating a language for a different species, consider what kind of sounds their language would encode.

Writing System

Now that we have our sounds, we are going to need some glyphs to encode that phonetic information. But we need to decide what kind of writing system we want to use. These writing systems primarily differ on how many sounds are expressed per glyph and what kind of information is encoded by the glyphs.

Here are your options:

Abjad: Glyphs exist only for their consonants. Vowels are meant to be inferred by the reader.

Real world examples: Arabic and Hebrew (though there are forms of writing vowels).

Abugida: A separate glyph for each consonant and vowel pairing. Vowels often are shown by diacritics (additional marks to the base letter).

Real world examples: Indic and Ethiopic.

Alphabet: A separate glyph for each consonant and vowel.

Real world examples: Our own romantic alphabet (such as English and Spanish).

Syllabary: Entire syllables receive their own glyph. Similar to but slightly different from an abugida.

Real world examples: Japanese and Cherokee.

Logographic: Separate glyphs for every word or phrase.

Real world example: Chinese.

Ideographic: Symbols that represent entire concepts or ideas.Real world example: “:)” and “:O”. Yep that’s right. Emojis. But also street signs or the no smoking symbol.

Featural: These ones are extra special. Featural glyphs encode phonetic information directly, such as using certain diacritics to determine whether a consonant sound is plosive. (These are for the really big linguistics fans out there.)

Okay. Our writing system is going to be an Abugida. I love the idea that vowels are simple marks added to the consonants rather than their own markings. So now for the fun part. Let’s make some glyphs!

Medium

When creating glyphs, it is important to consider what your people are writing on, writing with, and writing in.

Surface

If you are writing on paper with a pen, then you’ll likely get some flowy rounded glyphs. If they are chiseling into stone, then you’ll get a completely different look. Take a moment and think about what people will be writing on in your story.

For our language, I’m thinking of some sci-fi version of clay. Perhaps a substance that is soft like clay when an electrical charge is passed through it, but is rock solid when not. That allows our population to add some permanence to what they write.

We will call it Staticlay, because the naming department of my brain is apparently on vacation, and I’m already behind on my submission deadline for this article. (Sorry, Doug.)

Implement

This can be a brush, a stylus, charcoal, ink, or something altogether different.

I’m thinking that our script was first written in mud with farm tools. Then in clay tablets, and has now advanced to what it is today. I’m thinking that people began writing with a scythe or sickle. Slicing straight lines and using the round handle to mark dots.

(Adding some history worldbuilding here: They used straight lines because it is less natural and more easily noticeable. These tools soon evolved with stamps for specialized symbols–like our vowel diacritics–and now they use small hand sickles as writing implements)

It is also important to consider how convenience and time may affect how people use glyphs. So I’ll have a high script–which is the “proper” way–and a low script, which is more common and can be written with a pen and paper. Similar to how cursive writing in English speeds up the writing process.

Color

Color is a big part of our communication. If words are red, those of us with English as our native language might think they're urgent or the title of a romance novel. Blue words are probably the name of a social media company. Keep in mind that this differs based on culture. Red means anger, love, or lust to many of us in western society, but in Chinese culture it means good fortune. Consider how color might add different dimensions to your language.

For our conlang, let’s say they can dye Staticlay different colors for different purposes. Kind of like we do with traffic signs. Blue for connection and kindness, red for peace, yellow for offense, etc.

With all of that, let’s make some glyphs!

Boom! The five Universal Consonants, the five Possessive Consonants, our five vowel diacritics, and other marks needed for clarity and variety.

Now let’s name this thing. Using sounds from our newborn conlang, we will call it Moshlo.

Orthography

What information does your script encode?

There are a million things to consider with orthography, like:

- Sound

- Stress and emphasis

- Tone

- Volume

- Tempo

- Intonation

- Emotions

- Humor

- Inflection

But we will focus on these for ours:

Possession: This is going to be the big one for our conlang. You’ll notice that the first set of five consonants each have two dots. I started with that as a fun style choice but have decided they will be the “Universal” Consonants.

If a thing or concept cannot be owned, then it will start with a Universal Consonant. These consonants have two dots in high script.

The second set are the possessives. When a word starts with them, that thing can be owned or held. These glyphs have one dot in high script.

Word breaks: to simplify for the English/Spanish reader that I am, I will break words with spaces, but you might not break words apart at all for your conlang.

Spelling: I will assume that spelling has been standardized by this point in history. But remember that spelling was not always standardized and could be very fluid in the past. Keep that in mind for your worldbuilding.

Capitalization: Moshlo won’t have Capitals. But how do capitals change things in your language?

Punctuation: In the interest of simplicity for my brain, I think I’ll add “!” and “?” equivalents, as well as the “sentence end line.” This also can be very fluid of course.

Numbering: Ahh shoot! AHH SHOOT! How did I not think of this before… Numerology is a whole other ballgame. It’s fine. It’s FINE! We can skip it…

*inhales*

Okay, I can’t leave it alone. Sorry again, Doug. Lightning round!

Five has religious meaning to them, so it will be a base-five mathematical system. I’ll use the dots and lines and… boom!

Count the dots, crosses, and boxes as 1’s, 5, and 25’s. But wait… W

hat would five 25’s look like? No! I must stop here! Ugh, I’ll just write a different article on numerology. But for now we are MOVING ON! Onwards we go. Or rather on words we go. (Sorry not sorry, Doug.)

Words

For this step just open up a dictionary and Create a word for each word in said dictionary.

This is the longest portion of the process and goes hand in hand with the following grammar section. It is at this point where you must decide how far you want to take this conlang.

The advice from authors is to use a conlang only to the degree that it serves the story. So you might just have a relatively small dictionary of words that have meaning to your story rather than your own version of Merriam-Webster's. Of course if you want to go all the way with your language then by all means go for it! Just know that if this is for a fictional story, that's a huge time commitment on top of how long it takes to write a book.

Be sure to consider how specific aspects of your language may affect shared concepts. For example, because our consonants are broken up into universals and possessives, concepts such as time will have two words. Universal time and the time that one has in their life, day, or hour.

This would be an interesting way of conveying “can I have a minute of your time?” because the very concept of “your time” would be separated from the universal time.

We won’t go too crazy here, but here are some words that I’ve created. Notice which are universal and which are possessive.

Grammar

How do words interact?

For example, how do we note who is the giver of a greeting and the receiver of a greeting? Perhaps if the greeting is mine, then I would mark a dot above it and, if you are meant to be the receiver, I would mark a dot beneath “you” as shown below.

Next, how do we mark and vocalize when a word modifies another (like adjectives and adverbs in English)?

In “joyous greeting” below: joy is a modifying greeting. The two words are joined by the vowel sound “ah,” thus the modification is voiced and written. The blue color conveys connection.

CHALLENGE: Can you use the glyphs from above to pronounce this?

Here is a fun list of other things to mess with:

- Tense

- Root words

- 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person

- Nouns

- Verbs

- Proper Nouns

- Direct object pronouns

- Indirect object pronouns

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Punctuation with combined words

- Homophones

- Subjunctive vs. indicative

- Anything else you find in a grammar book

Contradictions and Rule Breakers

Keep in mind that, just like English, your language will have rules broken and exceptions all over the place. Add a few to make your language feel real and lived with.

Iterate

The best conlangs are truly deep and well thought out. This only comes through effort and iteration.

Here are some basic iterations as a final touch to our language:

In a spoken language, sounds change based on geography and culture. In my world, the people of the Southwestern Hills will flatten their “ee” sound to an “ih” sound, such as in “it,” and their “th” sound will sharpen to a “t” sound. This will make for some interesting accents and will allow people to identify origin based on an accent.

The high script loses favor and people drop dots from their writing because it slows things down. This leads to a loss of cultural meaning between that which can be owned and that which cannot, as the dots are what denotes that difference. Language scholars will even debate the importance of such information, like English users and the Oxford comma. (Oxford comma forever!)

Natural Languages vs. New Languages

One of the most important things you can do when constructing your own new language is to explore the world of language around you. According to The Intrepid Guide, experts know of 7,117 languages in the world!

You don’t need to look at each of those languages (though if you do, make a video about it because someone needs to), but you can unlock plenty of inspiration by exploring the vast world of languages.

Plenty of conlangs in popular media are based on real languages. In Dune, the language of the Fremen is based on Arabic. Frank Herbert did this for worldbuilding and lore reasons, and the effect is clear.

The Dothraki language from A Game of Thrones was inspired grammatically by Russian and based on Mongolian vocabulary. From this mix you can see the power of building up a language for a culture. The Dothraki are a nomadic, equestrian people, so Genghis Khan-era vocabulary would make perfect sense.

By mixing and matching from natural languages, you can build up your new language to fit the culture of the people you’ve created. Or you could start from a language and build the culture on that. After all, The Lord of the Rings was just an excuse to use the Elvish language that Tolkien came up with.

You don’t have to go through Tolkien lengths, but building a language can help skyrocket your worldbuilding and get you into the proper headspace to create your masterpiece.

Conclusion

If you need a good place to store all of your awesome conlang information, look no further than Dabble. You can basically create your own wiki and interlinking dictionary straight in our notes section, so you can always refer to it as you go along. Plus, with our new images feature, you can include all those awesome glyphs that you created right in your notes.

Finally, if you can’t get enough of conlangs, here are some awesome resources. I can’t recommend Atefexian’s YouTube Channel enough, he is the one who took me down this rabbit hole and the reason this article exists.

And here is some fascinating information on how English and accents change in different regions. It does a good job of showing how sounds differ and change over time in different geographical areas.

Thanks for joining me on this journey!

Now get out there and craft your language. Be sure to come back and tell me about it in our community. You'll find me hanging out in the fantasy and sci-fi spaces.