91+ Literary Terms Every Fiction Writer Should Know

As the title of this article promises, I'm about to hit you with over 91 common literary terms. You're going to get definitions, examples, and—in most cases—links to articles that go into more depth on each concept.

But first, let's be real with each other.

You probably learned some of these literary terms in school. Maybe the knowledge stuck with you long enough to ace the test, maybe it lingered a few years, but either way, I'm willing to bet that you're able to shape a decent story even if you can't identify every figure of speech included in your prose.

So why bother? Do you really need to study literary terms to succeed as a writer?

Kind of. But also, not exactly.

See, you can create situational irony without knowing that you're doing it. You can craft a dynamic and round protagonist without ever thinking, “Time to make this protagonist dynamic and round.”

But when you know literary terms, it's easier to hang. You can discuss your work clearly with critique partners, agents, and publishers, and contribute to thoughtful conversations about someone else's work.

Most importantly, studying literary terms makes you more aware of the many creative ways you can harness these tools to enhance your storytelling and style. You'll even find that you notice them more in other literary works, which will spark more ideas for using them in your own.

So let's do this. We'll take it category by category, covering the most essential literary terms from fiction-specific vocabulary to figurative language tools.

Time to jump in, figuratively speaking.

Essential Literary Terms for Fiction Writers

What does it mean to give your main character an arc? What's the difference between a hook and an inciting incident? How do you know if a character is tertiary?

Learn these fiction-specific literary terms, and you'll be ready to craft and discuss your novel like a pro.

Bonus Tip: You can get lots of practice talking craft in the DabbleU Campus, our free online community for brilliant writer types like you! Join us here.

And if you want to take it to the next level, check out the DabbleU Academy. Membership gets you access to in-depth courses, exclusive workshops, and more. To check it out, start a 14-day free trial at this link. That gets you full access to the Dabble writing tool and the Academy for two weeks, no credit card required.

Characterization Terms

Antagonist

An antagonist is a character who opposes the protagonist (main character) or creates conflict through incompatible beliefs and goals. A novel often has several antagonists, and they don’t have to be human. Opposing forces like nature, technology, and society count, too.

An antagonist can be malicious, deliberately intending to thwart the hero(ine), like Lord Voldemort in the Harry Potter series. Or it might simply be an unfortunate coincidence that this character can't pursue their own goals without getting in the way of the protagonist. (That's called an “unwitting antagonist,” by the way.)

Examples:

Darth Vader (Star Wars), Iago (Othello), King Triton (The Little Mermaid, unwitting antagonist)

Learn more:

Big Hurt/Ghost

The Big Hurt—also known as the “Ghost” or "Shard of Glass"—is a traumatic event in a character's backstory that continues to haunt them and influence their decisions throughout the current narrative.

The Big Hurt often represents the character's greatest fear or most crushing guilt. They typically live by a flawed philosophy (“The Lie Your Character Believes”) to avoid similar pain in the future.

Example:

In The Lion King, Mufasa's death is Simba's Big Hurt, especially since Simba thinks he caused the tragedy. He resists returning to Pride Rock, afraid to face the pain and fully believing that he's unworthy of the responsibility that comes with being king.

Learn more:

Character Arc

A character arc is a character's journey of growth or transformation over the course of a story.

There are four types of character arc:

- Positive arc (or moral ascending arc) - The character changes for the better.

- Negative arc (or moral descending arc) - The character changes for the worse.

- Transformation arc - The character remains essentially the same morally but gains tremendous abilities, often achieving hero status.

- Flat arc - The character doesn't change at all.

Example:

In The Lion King, Simba evolves from a carefree child with a glamorized view of power to a wise king who understands and accepts the responsibility of being a leader.

Learn more:

Character Archetype

A character archetype is a universally recognizable type of character that recurs in creative works across all cultures. The most common archetypes include:

- The Hero(ine)

- The Magician

- The Lover

- The Jester

- The Sage

- The Explorer

- The Ruler

- The Innocent

- The Caregiver

- The Creator

- The Outlaw

- The Common Person

- The Seducer

- The Orphan

Example:

Elsa from Frozen is a classic example of the Orphan archetype—she's had to fend for herself since childhood and, as a result, is a resourceful outsider with a pessimistic perspective.

Learn more:

Character Development

Character development is the gradual transformation of a character over the course of a narrative.

Example:

Throughout The Hunger Games trilogy, Katniss Everdeen evolves from an emotionally guarded loner who can only afford to focus on her family's survival to the leader of a rebellion with a deeper capacity for emotional connection and a more complex sense of personal responsibility.

Learn more:

Dialect

Dialect is a variety of language that reflects the community the speaker belongs to. Dialects can relate to specific regions, economic classes, ethnic identities, and more.

Rather than being an entirely different language, dialect is differentiated by rhythm, tone, grammar, accents, and specific words unique to the community. In dialogue, dialect is one of many tools for giving a character a unique voice that reflects who they are.

Example:

“You all,” “y'all,” “you guys,” “yous,” and “yous guys,” are all terms referring to multiple people in second person, yet their differences hint at the speaker's background, region, or social group.

Learn more:

Dialogue Tag

A dialogue tag is a phrase that indicates who is speaking. It can also describe how the dialogue is spoken.

Example:

“He said,” “she asked,” and “they bellowed” are all dialogue tags when paired with a line of dialogue.

Learn more:

Diction

Diction refers to the language style or choice of words used by a speaker. A character's diction is influenced by their age, level of education, cultural and social background, and personality. They may also alter their diction according to the situation they're in.

This may seem similar to dialect. An important distinction is that diction refers only to the speaker's word choices. Dialect, on the other hand, includes not just what they say but how they say it, including rhythm, tone, and accent.

Example:

A dreamy, creative character might speak in long sentences and use vivid metaphors, while a more straight-laced character might keep their speech brief, direct, and exact.

Learn more:

Dynamic Character

A dynamic character evolves over the course of a narrative. For better or worse, the events of the story spark internal change for them.

Example:

In Breaking Bad, Walter White makes a massive transformation from a mild-mannered chemistry teacher to a ruthless drug lord. Dynamic indeed.

Learn more:

Flat Character

Also known as a one-dimensional character, a flat character lacks complexity, doesn't change, and is only ever known for a few basic traits. If you can describe a character in a single word or sentence, like “plucky sidekick,” they’re a flat character.

This can be a tertiary (extremely minor) character who only shows up in one to three scenes and doesn't do much beyond delivering information, setting the scene, or adding humor. But you also see this kind of flatness in certain secondary characters, like generically evil villains.

Example:

Cinderella's wicked step-sisters are flat characters—a lot of meanness but no backstories, internal conflict, or growth.

Learn more:

Foil

A foil, or “literary foil,” is a character who highlights the traits of another character by exhibiting opposite qualities. Most foils are created to contrast with the protagonist.

Example:

In Black Panther, T'Challa and Erik Killmonger are foils. Both are passionate about protecting their community, but the juxtaposition of T'Challa's traditional, peaceful approach and Killmonger's radical, violent tactics encourages the audience to look more deeply at each character's backstory, motivation, and inner life.

Learn more:

Goal

A character's goal is the outcome they want to achieve. Characters have overarching story goals—like getting the big promotion or saving the world—and scene goals—like getting valuable information from a witness to a crime.

Example:

In The Lord of the Rings, Frodo Baggins's goal is to save Middle-earth by destroying the One Ring.

Learn more:

The Lie Your Character Believes

The Lie Your Character Believes—a term coined by K.M. Weiland—refers to the flawed philosophy a character embraces, sometimes out of ignorance but often in an effort to avoid repeating past trauma.

Also known just as the Lie, this is an essential component in a character arc, as it's through overcoming the Lie and embracing the Truth that a character transforms for the better. In negative arcs, they might instead reject the Truth or embrace a worse Lie.

Example:

In The Lion King, Simba believes he is the cause of his father's death and is unworthy of the throne.

Learn more:

Motivation

A character's motivation is the driving force behind their goals. In other words, a goal is what they want and motivation is why they want it.

Example:

In Rocky, Rocky's goal is to become a legitimate sparring partner for Apollo Creed. His motivation is to prove himself and rise above his working-class background.

Learn more:

Need

A character's Need is the outcome that will benefit them the most, often on an emotional or psychological level.

In many cases, their Need is not the same as their Goal. They spend the story relentlessly pursuing the Goal and discover the Need along the way.

Example:

In The Hunger Games, Katniss's Goal is simply to keep herself and her family alive. Over the course of the story, she realizes that what she needs is to form alliances and find both power and community in numbers.

Learn more:

Protagonist

Also known as a primary character, the protagonist is the main character of the story. Their desires, conflicts, weaknesses, and growth drive the plot.

Example:

Rachel Chu (Crazy Rich Asians), Bilbo Baggins (The Hobbit), Macbeth (Macbeth)

Learn more:

Round Character

The opposite of a flat character, a round character is complex. They have clear desires, motivations, fears, weaknesses, internal conflict, a backstory, and the capacity for growth. This makes them feel real to readers.

Example:

Moana (Moana) has clear goals and motivation, a complex personality, and experiences moments of self-doubt that audiences can relate to.

Learn more:

Secondary Character

A secondary character contributes to the story in a significant way, but the narrative doesn't center around them as it does the protagonist.

Example:

Piek Lin (Crazy Rich Asians), Gilbert Blythe (Anne of Green Gables), Gollum (The Lord of the Rings)

Learn more:

Static Character

A static character does not change over the course of a narrative. They remain consistent despite the events of the story.

Example:

Sherlock Holmes is a static character. There is zero transformation in his personality and perspective.

Learn more:

Supporting Character/Side Character

A supporting or side character is any character who is not the protagonist. This category can be further broken up into secondary characters and tertiary characters.

Example:

Mrs. Potts (Beauty and the Beast), Boo Radley (To Kill a Mockingbird), Piek Lin (Crazy Rich Asians)

Learn more:

Tertiary Character

A tertiary character is an extremely minor supporting character. This is a flat character who makes limited appearances but still contributes something to the story, such as filling out the world or delivering information.

Example:

Gunther from Friends, the members of The Lollipop Guild in The Wizard of Oz, the lady in Beauty and the Beast who needs six eggs

Learn more:

Story Development Terms

Act

An act is a major division in the structure of a narrative. Each act contains multiple scenes and story beats. It ends when a major event pivots the narrative in a new direction.

The three-act structure is extremely common in novels, plays, and especially film. However, you may also see works of literature that use a four- or five-act structure.

Learn more:

Beat

A beat is a significant event that moves the story forward. Beats work together to form a chain—each one is the result of the beat before and the cause of the beat that follows.

Example:

Simba's birth—the birth of a successor to the throne—is the first major beat of The Lion King. This leads to the second major beat: Scar orchestrates Mufasa's death and pins it on Simba to remove all obstacles between Scar and the throne.

Learn more:

Climax

The climax is the highest point of tension or conflict in a story, marking a turning point where the outcome is decided. This is typically when the protagonist applies what they've learned throughout the story to save (or destroy) the day.

(Side note: In rhetoric, 'climax' can also refer to a figure of speech where successive words, phrases, or clauses are arranged in ascending order of importance to build intensity.)

Example:

In The Wizard of Oz, the climax occurs when Dorothy defeats the Wicked Witch of the West.

Learn more:

Conflict

Conflict occurs when something stands between the protagonist and their goal. The protagonist is battling literally or figuratively against opposing forces, and they'll likely change as a result. The conflict is the heart of the plot.

There are two types of conflict: internal and external.

Internal conflict is the character's battle with themselves as they face down their own demons, overcome limitations, or confront questions of identity.

External conflict occurs between the character and an outside force, such as an antagonist, nature, or society.

Example:

The external conflict in The Truman Show is between Truman, who is seeking the truth about his reality, and Christof, the director who is trying to conceal the truth and keep Truman locked in a make-believe world. The internal conflict centers on Truman's own sense of identity and reality in a life that was orchestrated by someone else.

Learn more:

Dark Night of the Soul

The Dark Night of the Soul is a term commonly used to refer to the moment when the protagonist is at their lowest. It comes at the end of act two and is the beat where the main character reflects on their losses and ultimately makes the decision to move forward with a bold, new tactic.

Example:

In Anne of the Island, Anne’s Dark Night of the Soul occurs when Gilbert falls deathly ill and she realizes she loves him and may lose him.

Learn more:

Plotting Your Novel Using Save the Cat!

Denouement

The Dark Night of the Soul is a term commonly used to refer to the moment when the protagonist is at their lowest. It comes at the end of act two and is the beat where the main character reflects on their losses and ultimately makes the decision to move forward with a bold, new tactic.

Example:

In Anne of the Island, Anne's Dark Night of the Soul occurs when Gilbert falls deathly ill and she realizes she loves him and may lose him.

Learn more:

Denouement

The denouement is the resolution of a story’s plot. It follows the falling action and is the part of the story where the author ties up loose ends and shows the protagonist's new normal.

Example:

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy get hitched. That's the denouement.

Learn more:

Deus Ex Machina

Deux Ex Machina refers to a plot device where a seemingly unsolvable problem is suddenly resolved by an unexpected intervention.

This was common in Greek tragedies where gods would interfere with the affairs of humans. In modern storytelling, however, it's usually considered lazy.

Example:

While the book contained no such twist, the movie The Wizard of Oz revealed in the end that Dorothy's whole overwhelming experience was just a dream, allowing her to go home by simply waking up.

Exposition

Exposition is any and all essential background information on the character, setting, and circumstances of a story.

Example:

In the opening of Coco, Miguel explains the devastating event that caused his grandmother to banish music from the family—a detail that's essential for both the central conflict and the plot twist.

Learn more:

Hook

A hook is the opening of a literary work, designed to set the mood or tone, capture the reader's interest, and motivate them to keep reading.

When someone refers to a hook in the context of writing, they might be referring to a single opening sentence, an intriguing premise established immediately in a story, or the aspect of a story pitch or query letter that's most likely to snag someone's attention.

Example:

The first line of The Color Purple is, “You better not ever tell nobody but God,” a hook that immediately makes you want to find out what the secret is.

Learn more:

Inciting Incident

Also known as the Call to Adventure, trigger, or catalyst, an inciting incident is the event that sets the entire story in motion.

Example:

In The Hunger Games, Katniss's little sister is selected to be a tribute, the inciting incident that causes Katniss to volunteer in her place and fight for her life.

Learn more:

Midpoint

The midpoint is the middle point of a narrative. This is typically where a major reversal or revelation occurs.

Example:

At the midpoint of The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy meets the wizard only to learn that he won't help her until she murders yet another witch.

Learn more:

Parallel Plot

A parallel plot—also called a parallel narrative or parallel storyline—is an additional plotline complete with a protagonist, conflict, and story structure that is somehow related to a coexisting plot.

Example:

The Hours follows three parallel plots about three women living in different time periods. Their stories are linked by the novel Mrs Dalloway.

Plot

A plot is the sequence of events that make up a narrative.

Example:

Everything that happens in every story you've ever read or seen is the plot.

Learn more:

Point of View

The point of view (POV) of a narrative is the perspective through which the story is told.

A writer has several options when it comes to point of view, including telling the tale from a specific character's perspective or through the lens of an unnamed outsider. These options include:

Example:

The Great Gatsby is narrated in first person from Nick's point of view.

Learn more:

Scene

There are two different definitions of a scene in fiction writing.

A scene is most commonly known as a unit of storytelling that takes place in a specific location and at a particular time. When the location or time changes, a new scene begins.

However, this literary term can also refer to a storytelling unit in which the point-of-view character takes action. Specifically, they:

- Pursue a goal

- Run into an obstacle

- Encounter a new disaster

A scene may be followed by a sequel, in which the character reflects upon the events of the scene.

Example:

In one scene in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Harry tries to get through Aunt Marge's visit without losing his temper (goal). When she harshly criticizes his parents (obstacle), he loses his temper and magically inflates her like a balloon. Afraid of the consequences both at home and at Hogwarts (new disaster), he runs away.

Learn more:

Setting

A setting is the time and place in which a narrative occurs. This includes not only the physical attributes of the story's world, but also cultural, societal, and systemic considerations.

Example:

The setting of The Great Gatsby is the 1920s Jazz Age in New York, with all the social and cultural context that comes with that world.

Learn more:

Sequel

In the literary world, the term “sequel” can mean one of two things.

A sequel is most commonly known as a follow-up story that continues the narrative of a previous literary work.

The term also refers to a storytelling unit in which the point-of-view character reacts to something that occurred in a preceding scene. Specifically, they:

- Experience an emotional reaction

- Wrestle with a new dilemma caused by the previous scene

- Make a decision about how to move forward

Example:

In Breaking Bad, Walt creates a pros and cons list to decide whether or not he should kill someone. He's shaken by his circumstances (reaction), thinking through the problem those circumstances caused (dilemma), and ultimately chooses a path forward (decision).

Learn more:

Story Structure

The story structure is the framework of a story, setting up the sequence of events and how they relate to one another. There are several established structures all designed to hold the reader's attention and keep them on board for the protagonist's journey. Popular structures include:

- Three-Act Structure

- Save the Cat!

- The Hero's Journey

- The Fichtean Curve

- The Snowflake Method

- Dan Harmon's Story Circle

- Freytag's Pyramid

- The Eight-Point Story Arc

Learn more:

Theme

A theme is the larger message that an author seeks to convey through a literary work.

Example:

The theme of the movie UP is “Life itself is the ultimate adventure.”

Learn more:

Trope

A trope is a recurring theme, motif, or convention in a work of storytelling.

Example:

The Chosen One is a trope in which a character is destined to save the day due to their unique abilities. It's a trope because you see it over and over again throughout literature, drama, and film, from Harry Potter to Luke Skywalker.

Learn more:

Turning Point

A turning point is a story beat where a significant change occurs, sending the narrative in a new direction. Often, a turning point happens when the protagonist must make a new, difficult, or unexpected decision.

Example:

In Frozen, Elsa accidentally reveals her secret ice powers on her coronation day, forcing her to flee and live in isolation.

Learn more:

Worldbuilding

Worldbuilding is the process of creating the fictional world in which a story takes place. It includes everything from imagining the landscape to establishing the cultural setting.

This part of the writing process is essential in many forms of storytelling, though it’s especially important for speculative fiction like science fiction, fantasy, horror, and fairy tales.

Example:

J.R.R. Tolkien's Middle-earth is probably the most famous example of extensive worldbuilding. He developed everything from a history that spans thousands of years to multiple languages for the diverse races within his fantasy universe.

Learn more:

Advanced Literary Devices

Now that you know the basics for building a compelling story, let's give that puppy some layers.

Literary devices are tools that help you expose the deeper meaning of your story, evoke an emotional response from the reader, and reveal information in a more interesting way.

Some of these mechanisms involve adding new elements to your story while other literary devices merely come down to a simple figure of speech.

All of them can help you create a rock-solid storytelling strategy.

Symbolism Terms

Allegory

An allegory is a narrative that uses symbolic characters, events, and/or settings to convey a hidden meaning.

Example:

George Orwell's Animal Farm is a political allegory in which all the characters (primarily farm animals) represent figures in the Russian Revolution.

Analogy

An analogy is a comparison between two seemingly unlike things to make a point or deepen the reader's understanding of one or both of those things.

Example:

Just as a sword is the weapon of a warrior, a pen is the weapon of a writer.

Metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that creates a comparison between two unrelated things by stating that they are the same.

An extended metaphor is a comparison that goes on for a few lines, a paragraph, multiple pages, or even spans an entire book.

Example:

“My life is a perfect graveyard of buried hopes.” –Anne of Green Gables

Anne's life is obviously not a graveyard—it's a life—but through metaphor, she drives home the depth of her disappointment.

Learn more:

Motif

A motif is a recurring element or pattern in a literary work. Through repetition, this symbol, image, word, or phrase emphasizes a central theme or emotional journey.

Example:

Blood comes up a lot in William Shakespeare's Macbeth, creating a motif that symbolizes guilt and the consequences of ambition.

Learn more:

Personification

Personification is a literary device in which human attributes are given to non-human entities, including creatures, ideas, flora, and inanimate objects.

Example:

“Listen to the trees talking in their sleep.” –Anne of Green Gables

Simile

A simile is a type of metaphor that compares two different things using the word “like” or “as.”

Example:

“She entered with ungainly struggle like some huge awkward chicken, torn, squawking, out of its coop.” –The Adventure of the Three Gables

Symbol

A symbol is a common literary device in which an object, person, or concept represents something greater than its literal meaning. Symbols can help readers draw a connection between the events of a story and its deeper themes.

An author might also use a symbol to create a stronger emotional response since it's often easier for audiences to connect with the concrete representation of an internal experience than the mere idea of one.

Example:

In the famous mahjong scene in Crazy Rich Asians (movie, not book), a character's winning hand symbolizes their potential victory over their opponent in real life. (Heads-up: the linked scene contains major spoilers.)

There are also a ton of other symbols in this scene that are particularly meaningful for audiences familiar with mahjong.

Learn more:

Toying With Time

Anachronism

An anachronism occurs when something shows up in a time period where it does not belong.

We often think of an anachronism as being accidental, like when a historical fiction author accidentally references an object that would not have existed at the time their story takes place.

However, an anachronism can serve as a deliberate device for creating a comic effect, making a point, or helping modern audiences connect more deeply with the work or a historical event.

Example:

The series Bridgerton uses instrumental covers of modern pop songs as the actual music played in balls and parties.

Backstory

The backstory is everything that happened before a story begins. Backstory can shed light on several aspects of a narrative, including the harrowing events that built a dystopian society or the past trauma that motivates a character's decisions.

Example:

In the Harry Potter series, the backstory of Voldemort's attempted murder of Harry clarifies the reason for Harry's scar and illuminates the powerful connection between the two characters.

Learn more:

Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is a literary device in which the author creates anticipation by hinting at future events. This can be done using symbols, dialogue, and narration.

Example:

In Romeo and Juliet, Juliet says of Romeo, “If he be married / my grave is like to be my wedding bed.” Poor Jules is probably trying to be hyperbolic, but as we know, she does, in fact, end up in the grave not long after her nuptials.

Learn more:

Flashback

A flashback is a scene that depicts an event that occurred before the current timeline of a story to provide clarity, meaning, or emotional weight.

Example:

The Hunger Games contains a flashback in which the reader sees Peeta taking a big risk to help Katniss feed her family. This heightens the tension of the story, as Katniss now has to kill Peeta in order to survive and continue providing for her loved ones.

Learn more:

In Medias Res

In medias res is Latin for “in the midst of things.” This literary term refers to a storytelling technique in which the narrative begins in the middle of the action. It's a strategy that allows the reader to bypass the exposition and set-up, leaping into the fun stuff.

Writers who begin their story in medias res typically sprinkle in essential backstory as they go or through flashbacks.

Example:

The Illiad begins in medias res, opening in the midst of the Trojan War.

Learn More:

Experimenting With Irony

Comic Irony

Comic irony is a form of dramatic irony in which the audience holds information that a character does not have, leading to humorous situations.

Example:

The movie Coming to America is loaded with this type of irony. The audience knows Akeem is royalty, but the people he encounters in New York City believe he's the child of goat herders. As a result, those characters underestimate his status, education, and capability to comic effect.

On the flip side, Akeem is finding a way in a world that's more familiar to the audience than it is to him. His misinterpretation of NYC and American culture is good for a lot of laughs.

Learn more:

Cosmic Irony

Cosmic irony is a form of situational irony. In situational irony, the outcome is different from what is expected. When it comes to cosmic irony specifically, that unexpected outcome seems to have been orchestrated by fate, the universe, or higher beings.

Example:

While most people would predict that a love story would end in a “happily ever after,” Romeo and Juliet ends in death. The texts suggests this romance was ill-fated from the beginning, referring to the pair as “star-crossed lovers.”

Learn more:

Dramatic Irony

Dramatic irony occurs when the audience holds crucial information that a character (or characters) does not have.

Example:

In The Truman Show, the audience is aware that Truman's entire life has been televised around the world. Truman, however, does not know this, and tension builds as we wait to find out when he'll learn the truth and what he'll do about it.

Learn more:

Hyperbole/Overstatement

Hyperbole—also known as overstatement—is a form of verbal irony in which the speaker or writer exaggerates reality to make a point.

Example:

The phrase “buried under paperwork” is an overstatement. The speaker isn't literally covered in a mound of paperwork (we hope), but the work is so overwhelming it feels like being trapped and having to dig their way out.

Learn more:

Sarcasm

Sarcasm is a form of verbal irony in which the speaker says the opposite of their literal meaning, typically as a way to mock or complain.

Example:

If someone said, “Nice weather we're having” while hunkering down in a cellar during a tornado, that would most definitely be sarcasm.

Learn more:

Situational Irony

Situational irony occurs when the outcome is different from (and often the opposite of) what one would expect.

Example:

In “The Story of an Hour,” Louise survives the news of her husband’s death despite having a heart condition that makes her very delicate. In processing his death, she begins to welcome her newfound freedom. Then, when she discovers that a mistake has been made and her husband is, in fact, alive, she dies from the shock of it.

In the end, it’s not her husband’s death that’s too much to take. It’s his survival.

Learn more:

Socratic Irony

Socratic irony is a form of verbal irony in which a person feigns ignorance to expose someone else's incompetence, corruption, or inconsistency.

Example:

In “A Modest Proposal,” Jonathan Swift pretends to think selling poor Irish babies to English nobles as food is a great solution for widespread poverty in Ireland. By delivering this proposal with feigned sincerity, Swift highlights the callous exploitation of the Irish people at the hands of the English.

Learn more:

Tragic Irony

Tragic irony is a form of dramatic irony in which the audience has crucial information that a character does not have and is painfully aware that the choices the character makes in ignorance will lead to tragedy.

Example:

Romeo and Juliet's tomb scene is an example of tragic irony. The audience knows Juliet isn't really dead, so they can only watch with horror as Romeo drinks poison, unwilling to live without her.

Learn more:

Understatement

An understatement is a form of verbal irony in which the speaker minimizes the truth to make a point.

Example:

When someone meets up with an old friend they haven't seen in four years and says, “It's been a minute!”, they're making an understatement.

Verbal Irony

Verbal irony occurs when a person says something different from their literal meaning. The speaker intends for their true message to be understood either immediately or eventually.

Example:

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” –Pride and Prejudice

This snarky opening line pokes fun at the frenzy that ensues among single women and their parents when a wealthy single man is on the scene.… at least in an era when women had very few options for gaining financial independence.

In truth, it's not rich men who are looking for matrimony; it's the unmarried women who are looking for a rich man to secure their future through marriage.

Learn more:

Crafting a Unique Writing Style

Let's get down to the nittiest and grittiest literary terms. We're going to talk about the tools you can use to create nuance in dialogue, draft engaging narration, and shape your signature writing style.

In a moment, you'll learn several literary devices that will help you play with voice and tone. But first, we'll take a look at the terms that are specific to your chosen genre and format. After all, unlocking your unique style begins with knowing how to define your work and where it fits in the market.

Genre and Format

Flash Fiction

Also known as micro-fiction, flash fiction describes a work of fiction that is 1,500 words or less.

Example:

“The Huntress” by Sofia Samatar is a work of flash fiction that clocks in at a mere 374 words.

Genre

A genre is a category of dramatic or literary work defined by its tone, content, and style.

Example:

The broadest and best-known literary genres include:

Learn more:

Novel

A novel is a long work of fiction that tells a complex and detailed narrative, typically with several well-developed characters and multiple plot lines.

Example:

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen, Beloved by Toni Morrison, Outlander by Diana Gabaldon

Learn more:

- How to Plan a Novel

- Let's Write a Book (This is a 100-page ebook on planning and writing a novel. Click the link to download it for free.)

Novella

A novella is a work of fiction that's shorter than a novel and longer than a short story—typically somewhere between 17,000 and 40,000 words.

Example:

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck is a novella at 30,000 words.

Learn more:

Parody

A parody is a comedic and/or satirical imitation of a specific work, style, or genre. It may pay homage to the source material that inspired it or it might set out to mock the original. Sometimes it does both.

Example:

Crazy Ex-Girlfriend is positively packed with song parodies, like this amazing empowerment anthem, in which the “face your fears” message includes tips like “run with scissors” and “fly out of a window.”

Short Story

A short story is a brief work of fiction that typically (but not always) focuses on a single plot line and protagonist. The standard length for short stories runs between 1,500 and 10,000 words.

Example:

“The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson is a short story at 3,775 words.

Learn more:

Subgenre

A subgenre is a category within a genre that represents a more specific style, theme, setting, or tone. Many subgenres also come with their own tropes.

Example:

The romance genre includes subgenres such as romantasy, historical romance, paranormal romance, and romantic comedy.

Learn more:

Prose

Alliteration

Alliteration refers to the repetition of the same sound at the beginning of adjacent or closely connected words.

Example:

“The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew, / The furrow followed free.” –Rime of the Ancient Mariner

You hear repeated sounds in “breeze blew,” “foam flew,” and “furrow followed free.”

Learn more:

Allusion

An allusion is a brief reference to a person, place, thing, or idea of historical, cultural, literary, or political significance.

Example:

If someone referred to their vacation home as their “Garden of Eden,” that would be an allusion to the Garden of Eden in the Biblical creation story. Anyone from a culture in which that story is common knowledge would immediately understand that the speaker is calling their vacation home a personal paradise.

Assonance

Assonance refers to the repetition of the same vowel sound among adjacent or closely connected words.

Example:

"The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain."

The long “a” sound repeats in “rain,” “Spain,” “mainly,” and “plain.”

Learn more:

Cliché

A cliché is an overused phrase that has lost its impact due to frequent use. You want to avoid clichés in your writing.

Example:

If you say someone is “cold as ice,” “a diamond in the rough,” or “a kid in a candy store,” you're using a cliché.

Learn more:

Connotation

Connotation refers to the feeling or idea a word evokes beyond its literal definition.

Example:

The literal definition of “home” would be the physical location in which a person lives, but the connotation of “home” might be a warm and welcoming place where that person can truly be themselves.

Consonance

Consonance refers to the repetition of the same consonant sound among adjacent or closely connected words.

Example:

The phrase “pitter-patter” contains three instances of consonance with the repeating “p,” “t,” and “r” sounds.

Learn more:

Denotation

Denotation is the literal dictionary definition of a word without any emotional associations.

Example:

The denotation of “cheap” is “low in price.” That's it. Simply a fact.

Imagery

Imagery refers to the use of descriptive and figurative language to create mental images that appeal to the senses and evoke emotion in the reader.

Example:

Robert Frost’s poem “Birches” is full of vivid imagery like this:

“Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells

Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust—

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You'd think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.”

Learn more:

Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is a literary device in which two opposing ideas or things are placed in close proximity to one another for contrasting effect.

Example:

The opening line of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities is one of the most famous examples of juxtaposition:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness...”

Figure of Speech

A figure of speech is a word or phrase used non-literally to make a point, create a mental picture, evoke an emotion, or highlight an idea.

Several of the literary terms in this list fall under the category of figure of speech, including metaphor, personification, and hyperbole.

Example:

It's a figure of speech to say, “Time is a thief.” Time is not literally a thief, but the passage of time can make us feel like opportunities, experiences, and even loved ones have been stolen from us.

Mood

Mood refers to the overall emotional tone or atmosphere of a written work. The content, word choice, and rhythm of the writing all contribute to the tone.

Example:

A scene between two whispering lovers taking a walk in a vineyard at sunset is likely to have a romantic mood.

Learn more:

Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia refers to a word that imitates the actual sound it describes.

Example:

“Hiss,” “clang,” and “thud” are all onomatopoeia.

Paradox

A paradox is a figure of speech in which two seemingly contradictory ideas reveal a truth.

Example:

“You have to spend money to make money.”

The act of spending money seems contradictory to the goal of making money. But in reality, a business that invests strategically in things like product development and marketing may be more profitable in the long run.

Parallelism

Parallelism is a literary device in which multiple sentences or phrases use the same grammatical structure.

There are several rhetorical devices that fall under the heading of parallelism, such as epistrophe, which involves the repetition of words at the end of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences to create emphasis and rhythm.

Example:

“...a government of the people, for the people, by the people…”

By using a parallel structure (and epistrophe!) where he repeated the same phrase with different prepositions, Abraham Lincoln emphasized the importance of preserving a nation built around its people.

Purple Prose

Purple prose refers to writing that is so flowery or elaborate that it distracts from the content and takes the reader out of the world of the story.

Example:

"The ethereal moonlight tenderly caressed the velvety blush of her cheek as a gentle zephyr whispered through the fragrant, violaceous blossoms."

Learn More:

Show, Don't Tell

“Show, don't tell” is common writing advice for using sensory images to draw the reader into a scene and create an emotional experience rather than simply telling the audience what the moment was like and how they should feel about it.

Example:

This is simply telling:

“The OR waiting room was an unpleasant place that made her feel tired and sad.”

This is showing:

“She spent four hours under the fluorescent buzz of the OR waiting room, her limbs heavy and her mouth sour from stale coffee.”

Learn more:

Subtext

Subtext refers to the unspoken, implied meaning beneath the words that are actually said or written. It can be a tool for crafting realistic dialogue and for writing a story that feels authentic to your readers.

Example:

Imagine your mom says, “You're so busy lately!” Her true meaning might be, “You're not calling enough.” That would be her subtext.

Learn more:

Tone

In both dialogue and narration, tone refers to the speaker or narrator's attitude towards what they're saying.

Example:

“...for not even a brook could run past Mrs. Rachel Lynde's door without due regard for decency and decorum…” –Anne of Green Gables

The playful use of hyperbole sets a lighthearted and amused tone early in the novel.

Learn more:

Voice

In both dialogue and narration, voice refers to the style in which someone communicates.

This includes details like diction, pacing, rhythm, tone, body language, and even the literal sound of their voice.

Example:

“She cursed me at such length and with such inventiveness I had to check both my watch and my dictionary.” –The Sympathizer

From comedic content to artful sentence structure to diction that demonstrates high intelligence without sacrificing clarity, Nguyen establishes a voice that shows his nameless narrator's insight, detachment, and dark humor.

Learn more:

Poetic Devices

Free Verse

Free verse is a style of poetry that doesn’t follow a fixed rhyme scheme or consistent meter. The writer is free to shape line breaks and pacing however they like. This allows for a more natural flow, which is why free verse often reflects the rhythm of everyday speech more than traditional verse forms.

Example:

Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “The Fish” is a famous example of free verse poetry with lines like these:

“He hung a grunting weight,

battered and venerable

and homely. Here and there

his brown skin hung in strips

like ancient wallpaper…”

Internal Rhyme

Internal rhyme occurs when two or more words rhyme within the same line of poetry, rather than just at the end of lines. This can add emphasis, create rhythm, or even produce a comic effect.

Internal rhyme is used most often in poetry and song lyrics, but you can also use it in prose to add subtle musicality to narration or dialogue.

Example:

“Double, double toil and trouble…” –Macbeth

The internal rhyme is the thrice-repeated “ubble” sound in “double” and “trouble.”

Meter

Meter is the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that helps establish a poem’s rhythm. Stressed syllables are those spoken at a higher volume, higher pitch, or with greater emphasis, and unstressed syllables are those spoken with less volume, a lower pitch, or less emphasis.

As the poet, you don’t get to decide which syllables are stressed or unstressed. It’s inherent to the language. You can hear it yourself in words like (stressed syllables in bold) cocoa, bulldozer, and arrest.

Instead, your job is to make sure the words you choose accommodate the meter you’re trying to create.

Example:

Some poetic styles follow the same meter. Iambic pentameter is a famous one.

In iambic pentameter, a line consists of ten syllables. Every other syllable is stressed, beginning with the second one, like this:

“Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”

Rhyme Scheme

A rhyme scheme is the pattern of rhyming words at the end of each line in a poem or song. We use letters to indicate which lines rhyme with each other within a specific rhyme scheme.

For example, a four-line stanza with an ABCB rhyme scheme means the second and fourth lines rhyme. A limerick has an AABBA rhyme scheme, where the first, second, and fifth lines all rhyme, as do the third and fourth lines.

Rhyme schemes help create musicality, structure, and emphasis in poetry. They can also be used in narrative poems, song lyrics, or even playful prose to add a sense of rhythm.

Example:

A lot of your favorite songs probably feature straightforward rhyme schemes like ABAB or ABCB. But this stuff can get pretty wild.

Robert Frost’s poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” features a rhyme scheme that carries one rhyming word from one four-line stanza to the next, like this:

“Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

“My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.”

Notice how the “here” in the first stanza rhymes with “queer,” “near,” and “year” in the next stanza? That continues for the full poem, creating an ABAA BBCB CCDC DDDD rhyme scheme.

The Art of Literary Analysis

Now let's talk about how to use all these literary terms you just learned (or rediscovered).

It's true for every aspect of the craft: the more you read, the better you'll write. By seeing how other storytellers put these concepts to work, you'll uncover new methods for using literary devices and get inspired to do your own experimentation.

So by all means, start testing these mechanisms out in your current work-in-progress. But as you do, make an effort to do some active reading. Pick up a book and resist the urge to just melt into the story.

Instead, use these techniques for analyzing and learning from literary works:

Structure and Character Development

As you read, notice how the author indicates things like:

- Character goals

- Motivation

- Backstory

- Ghosts

- Lies

- Transformation

See if you can identify:

- Exposition

- Foils

- Archetypes

- Antagonists

- Secondary characters

- Tertiary characters

Pay attention to the way the story is set up. Do you recognize different story beats? Are you able to lay out the plot in one of the story structures you learned?

Actually make notes as you read. Reflect on what worked, what you would have done differently, and which strategies you'd like to try for yourself.

Literary Devices

When you notice a specific literary device in something you're reading, pause to examine it. Ask yourself:

- How does the use of this device influence the reading experience?

- Why might the author have chosen to use this tool in this way?

- Do I think it works well? Is there a different strategy I would have used instead?

If you admire what the author did, write it down! If it's a big-picture device like dramatic irony, describe how the writer handled it and how it influenced your experience of the story. For something brief like a clever figure of speech, go ahead and write it down word-for-word.

If keeping an eye out for literary devices in general is too broad of a goal, pick just one to three terms that you're interested in exploring more. Sometimes a much narrower goal makes it easier to notice examples.

And as you do all this analytical reading, remember that our big list of literary devices has tons of links where you can learn more about the terms we discussed.

So don't be shy! Get in there, learn as much as you can, and practice even more.

In fact…

Stick With Dabble and Keep Improving Your Craft

We at Dabble are all too familiar with the insane amount of work that goes into developing your writing skills and drafting a novel. That's why we've created a ton of resources to support you on your journey.

Not only can you access loads of free information in DabbleU, you can have tips and writing prompts sent right to your inbox every week! All you have to do is sign up here for our newsletter.

Did I mention we have a free ebook that walks you through the entire novel-writing process? Click here to snag that. You can also swap insights, resources, and encouragement with your fellow writers in our online community, the DabbleU Campus.

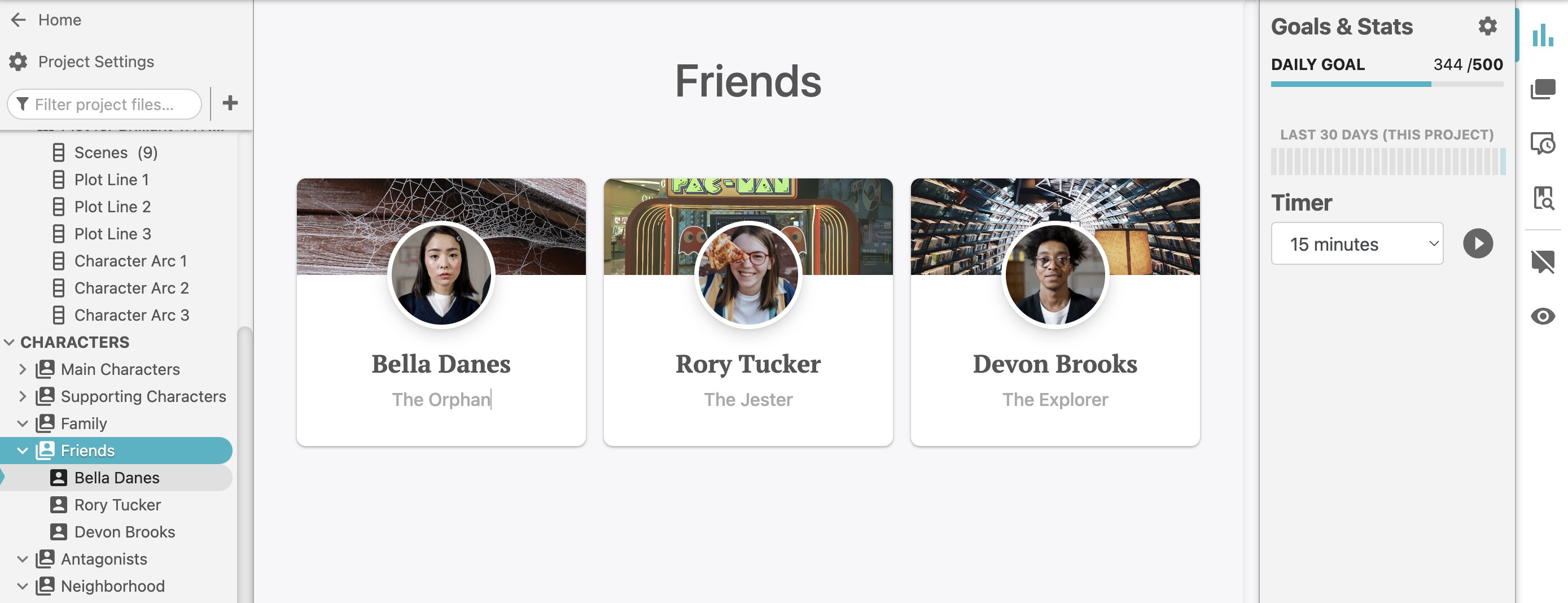

And if you'd like a little help staying organized and motivated as you plan, plot, and draft your book, the Dabble writing tool can help. This thing has you covered for every part of the process with incredible planning and editing tools, including character profiles, Story Notes, and the famous Plot Grid.

Best of all, you can try everything this tool has to offer and get access to the DabbleU Academy absolutely free for 14 days. Just click this link to get started.